It was kind of you, N, to ask for my advice on writing essays, even though I might not be the best person to give such advice. As you know, I have been writing stories for as long as I can remember and my beginnings are obscured by the haze of childhood and teenage years now.

Still, I might be able to say a few things thanks to the sheer amount of time I've spent writing and honing the craft. After twenty years, it might be safe to say that I'm a storyteller before I am anything else. Not only is it the most entertaining out of every creative endeavour I've tried, it's also a wonderful coping mechanism, a method for reflecting and understanding life, the universe, and everything. Murakami Haruki says that writing allows him to think better, that he couldn't think as well if he didn't write, and I am the same.

There are scores of writing advice out there. We love hearing about different processes and routines to inspire us, as no one approaches the craft in quite the same way. When asked for advice, all we can do is show what works for us and hope there will be something useful or inspiring in it for others.

My aim is to show how I write the essays you can read on Occam's Lab, after which I will introduce some very different processes that have worked for other writers so you may experiment with any that speak to you and arrive at your own answer to the question: How should I write?

How I write

First, I get an idea, often from places or experiences in daily life but also from books, film, games, music, theatre, or anything else I consume. I jot it down in a new note with a working title that describes what I think the essay will be about. This might change later. The first idea might be a single concept, a question to explore such as From Penny Dreadfuls to Paperlike, or a unique chain of associations such as Morphine Lollipop and In Praise of Japanese Living.

Sooner or later, my notes start to show a clear beginning, middle, and end, at which point I move from bullet points to full sentences. I draft the essay and fill in the details, formulating arguments and adding quotes.

After a lot of trial and error, I know that my pieces turn out better if I map them onto some sort of narrative structure or framework—I do this for fiction, using the Save the Cat beat sheet, as well as for nonfiction, using a framework I learned from Dan Koe in his Two Hour Writer course.

a hook that captures attention, ideally the first sentence

introducing the core concept: an answer, conclusion or big idea

3+ arguments that prove the conclusion, with facts, data, anecdotes, quotes etc. that support these arguments

the conclusion

I prefer this simple framework because it’s flexible and applicable to different types of creative nonfiction. You could write a listicle, a personal essay, or an opinion piece. If my idea doesn’t fit the framework at all, I ignore the rules and go with my instinct1.

Since most of my planning happens before drafting, my essays require little editing. If I am unsure about some aspect or other, I share the unpublished draft and ask for feedback in online writing communities. Most of the time, I only tweak the phrasing and eliminate typos before transferring the essay into the Substack editor and scheduling publication.

The Highly Structured Example

No matter how much you read about process, it’s always easier to visualise with examples. To give you a better idea, I will show how I carried two of my recent essays from initial idea to publication.

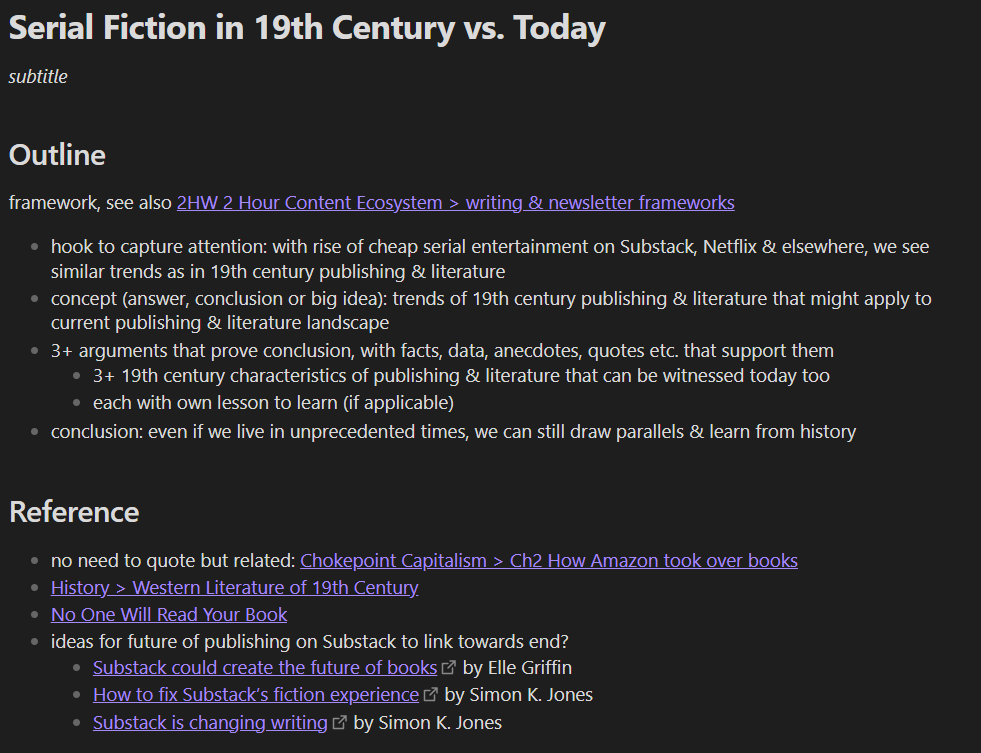

From Penny Dreadfuls to Paperlike started as a few bullet points based on the framework introduced earlier as well as some links to book chapters or articles I had read previously, that I thought would fit the topic2. Note that the original title was more descriptive but less catchy. Since Substack allows titles as well subtitles, I like using something catchy that hooks readers as title and an informative phrase or sentence that reveals more about the topic as subtitle.

The outline grows as I refine the idea. Hook, concept, and conclusion stay the same but I start filling in the arguments and even adding one counter-argument. At this point, the links lead to my personal notes on sources I want to use. I also note in italics if any parts are lacking quotes to be researched or looked up later.

I start drafting the essay from this outline, using “1st argument”, “2nd argument” as placeholder headings because I can’t think of anything good in the moment. At this point, the links are changed to actual source weblinks. In this case, I came up with the essay title and headings comparatively late, after brainstorming several options.

This piece marks the first time I asked beta readers for feedback prior to publication. Their helpful comments led to some more light edits and taking out the counter-argument, as they felt it didn’t fit here and could even be expanded into a separate essay. After one final read-through, I hit publish.

The Association Chain Example

In Praise of Japanese Living started as a simple idea. Many creators, myself included, get some of their best ideas from associating two or more disparate concepts in a surprising way. In this case, it was the aesthetics of the average Japanese home and what I remembered reading on Japanese interior design in Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s classic In Praise of Shadows. Because of this, I also knew early on that my title would be In Praise of Japanese Living, referencing Tanizaki. Two other associations were Tokyo Style as well as an article by Matt Alt I’d read only a few days before.

A chain of associations cannot be mapped onto the framework I use for other pieces. Instead, I thought about which ordering would make the most sense. The hook, of course, would be my personal experience of walking the neighbourhood that kickstarted my curiosity about Japanese architecture and aesthetics.

After a personal example, backtracking to a literary quote describing a general concept makes for excellent contrast—hence I followed with Tanizaki on beauty. Discussing traditional architecture provided a natural transition to Tokyo Style etc.

As a caveat, it’s rare that an essay springs into my mind fully formed like this one did. Most of the time I take a lot more notes, do research, add or discard ideas and arguments, narrow down or change the focus and much more before the piece is finished. This is why some sort of framework is crucial to me: the hook, central concept, and conclusion provide the structural foundation and scaffolding to support my ideas and thoughts.

Finally, I decided on using Roman numerals as headings—something I enjoy doing for more freestyle or personal essays because it lends a literary (or pretentious) quality.

Excluding the time ideas were rolling around in my head, I worked on In Praise of Japanese Living from November 22 to December 1, the day I hit publish. Most pieces, however, stay in my drafts for much longer. Since I work on multiple pieces at the same time, whatever I finish first gets published next.

How others write

Now that you know my writing process, let me introduce a handful of others. Some are phrased as advice but remember, take what works for you and leave the rest. You will see that some contradict each other as well. There is almost no universal writing advice, it’s all dependant on genre and audience.

David Perell, a nonfiction writer and writing teacher, has a 10-step process from collecting ideas to publishing. I also enjoy his podcast How I Write, where he interviews other writers on their ideas and process, discusses and analyses their best pieces etc. Every single interview is full of great lessons and inspires me to improve my own craft!

Nat Eliason ran a successful weekly newsletter for years before he wrote and published Crypto Confidential, a memoir on his adventures in the crypto world. His learnings from writing that book are summarised in an excellent deep dive on writing better. I recommend taking a look at the table of contents and skipping around, as some tips on book writing might not apply to you.

Prolific fantasy author Brandon Sanderson has a writing FAQ on his website—while it is geared towards fiction, much can be applied to nonfiction as well. The two pieces I would recommend are his general advice for new writers as well as his take on outlining vs. free-writing. In fact, his process of working with what he calls a “floating outline” is similar to mine, only his outlines are much more detailed.

If you prefer books to online resources, here is a list of my favourite writing guides.

On Writing Well by William Zinsser

On Writing by Stephen King

Save The Cat! Writes A Novel by Jessica Brody

The Art and Business of Online Writing by Nicolas Cole

If I had to recommend only one book, it would be On Writing Well by Zinsser. It’s easy to lose yourself reading but keep in mind to also act on what you learn and try out all that advice for yourself.

Bonus: How to get unstuck

Lastly, whatever your process looks like, you will get stuck. It’s inevitable and it happens to all of us. Here are some techniques for getting unstuck that have worked for me.

Write some sentences or paragraphs by hand.

Stop writing and do something else for a while. Something physical, like going for a walk, is particularly helpful. Moving your body, with your mind at rest, is a great recipe for ideas and problem solving in general.

Read something by an author you admire.

Try to define what is not working in one short question, then brainstorm 3-5 possible answers. I learned this technique from Rachael Stephen, who calls it the magic question. Brainstorming is best done using pen and paper too.

Try to describe the problem to someone else (a friend or even your cat). More often than not, the act of describing it will bring greater clarity on what it is you’re struggling with and how to get past it.

Work on something else for a while—the main reason why I always have multiple pieces in my drafts. This can backfire though. If you have trouble finishing things, I strongly recommend you only work on one piece at a time!

I hope this has given you some ideas and tools to figure out your own writing process. Let me know if you’ve tried or are trying one or more approaches mentioned here. I would love to hear from you, N, and from anyone else how you’re faring in your efforts to tame your thoughts, to pin them down on the page—never an easy feat.

All the best in your endeavours,

V

You have to know the rules before you can break them though.

Spoiler: Not all of those made it into the finished article.

Vanessa, this piece immediately resonated with me, not just for the depth of your process but for the way it opens with a direct pull from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “life, the universe, and everything.” The reference hooked me, but it’s the care you took in layering your own voice with outside influences that kept me reading. I’ve always found podcasts about life and writing to be a fascinating medium for understanding creative work—hearing how others construct their processes always feels like peering into a blueprint for a house you’ll never live in but deeply admire. Your transcription and audio options are also appreciated more than I can articulate. The ability to engage while on the move—reading in the in-between spaces of my own life—feels like a small act of grace in a world overloaded with content. Thank you for sharing your work and Happy New Year!